Che, Fidel and Me

Version of an article written by Peter Davis from the International Times - Winter 2009

What was Cuba like in the Sixties when the Revolution was young? A veteran filmmaker shares his memories.

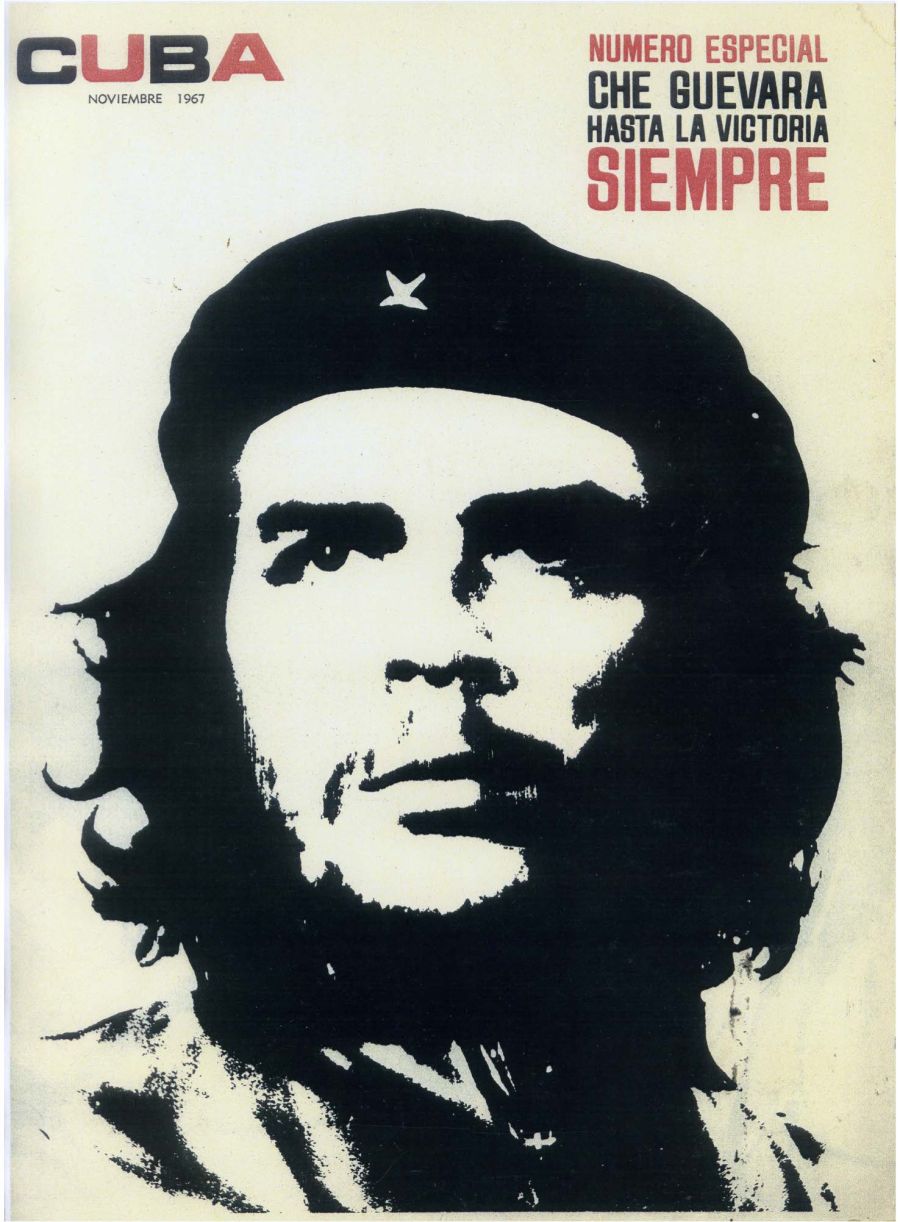

Che, CUBA Magazine (front cover), November 1967

I name-dropped Che to lure you into reading this. Who can resist the magic of the name? Certainly not Hollywood, as the latest hagiographic Che shows. Actually, my direct contact with Che lasted just a little bit longer than it will take you to read about it, but it will serve to draw you into my first visit to Cuba in 1964. I was there to film anything about Cuba for Swedish Television. On the evening of April 30, I made my way down to the Plaza de la Revolución to scout the location where I would be filming the great First of May parade the next day.

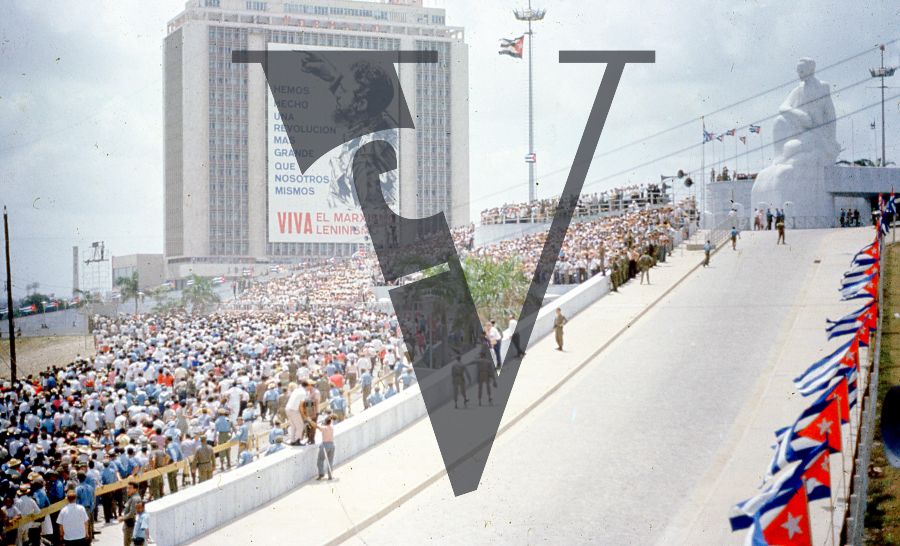

When I got there, a few workmen were putting the finishing touches to the podium where the speeches would be made, opposite the grandiose José Martí memorial looming over the Plaza, but the huge open space was virtually empty of life. Approaching the bleachers where the leaders of the revolution would sit on the morrow, I noticed one lone figure seated there. It was Che. He was there for—what? I suspect, a moment of contemplation before appearing before the masses tomorrow. He saw my camera, and there was a moment of mutual recognition, he of my profession, I of his Cheness. I felt it would have been intrusive at the moment even to take a picture. Yet he was the only man I have ever seen who truly had charisma.

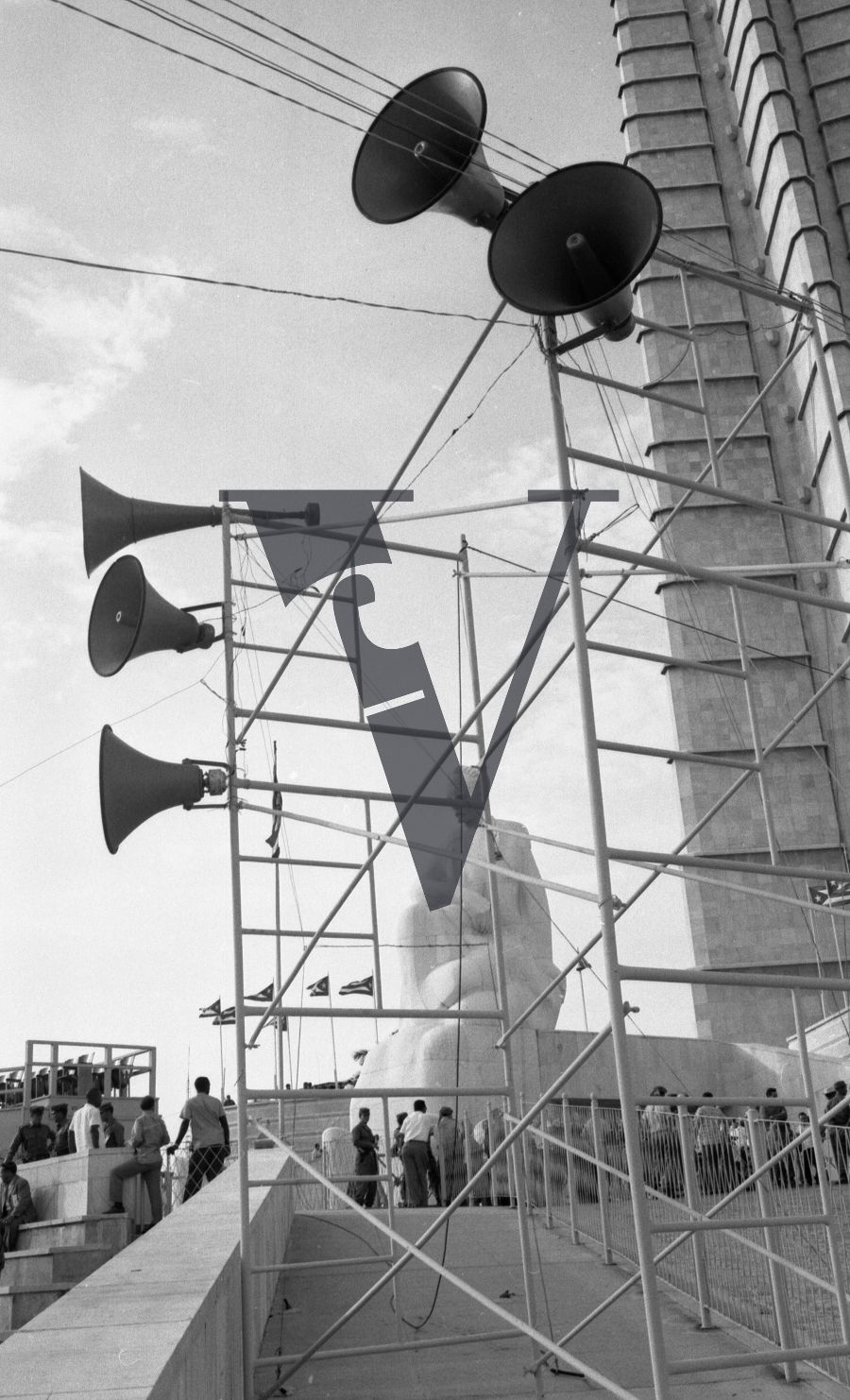

I filmed him the next day, together with Fidel, during the exhausting parade of milicianos and milicianas bearing weapons, bandanaed workers, drum majorettes with their uniquely Cuban swing of the hips, oceans of flags, miniskirted students, and cane cutters brandishing wooden machetes—the masses of the Revolution. A float flaunted a hook-nosed Uncle Sam being kicked by a Cuban miliciano. This was some years after the aborted Bay of Pigs invasion, and Cuba was still under frequent attack by gusanos, “worms”— CIA-backed terrorists. The final image of my film would be taken from the parade, a giant poster of Fidel borne forward until it fills the whole frame, domineering and menacing.

Starting from being supportive of the revolution, I had, after some weeks in Cuba, modified my position considerably. I was turned off by the empty shelves in local stores, where, in a tropical country, even oranges were rationed (Che was responsible for this, he was Minister of Agriculture); where neighbours spied on neigh- bours for un-revolutionary conduct; and the complete ban on critical expression: “Within the Revolution, everything; outside, nothing.”

The film I made at that time I called Cult and Culture. It was a look at Cuba’s new revolutionary culture, and at what I came to see as the dominance of the Fidel cult of personality, in the Latin American caudillo tradition. What was positive was a flourishing of the arts. This seemed most successful in the creation of a new national cinema, an about-face from what had primarily been a pornographic film industry in the old sin city of Havana. In a few short years, ICAIC, the Cuban film institute, had nurtured Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, Santiago Álvarez, Eduardo Manet, Alberto Roldán, Fausto Canel, Jorge Fraga… Missing from this list is the great Néstor Almendros, who was too independently minded—“outside, nothing”. Besides Cult and Culture, I made a programme about contemporary Cuban cinema, which was establishing itself along the lines of the New Wave from France and the Italian neo-realist tradition.

There were many foreigners there at that time, offering their skills to the revolution. I recall answering an invitation from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to take part in a cane-cutting expedition, which gave me a direct appreciation of the punishing demands on the body of that occupation. The Cuban character seemed down-to- earth, although the universal address of “compañero” concealed a society that was not as egalitarian as it wanted to appear: there were clearly discreetly privileged people in Cuba. Rhetoric as a discipline, largely forgotten in Anglo-Saxon societies, was alive and well in Cuba. Listening to eternal polemics in casual conversations, I always wondered how they ever managed to stop talking long enough to make a successful revolution. You cannot understand Fidel without appreciating his appeal as a master of rhetoric, deep-rooted from his university days.

I had had pretty much free rein in this 1964 visit, no interference by the authorities; helpful, even. Things changed with my next visit in 1967. This time, I was working as an independent for UPITN (United Press International Television News), for whom I had offered to cover the Congress of Intellectuals to take place in Havana beginning January 10, 1968. By this time, Che was dead, executed some months before. (Later, I would do an interview with Eric Fromm, the renowned psycho- therapist, who in passing mentioned Che’s debilitating asthma as being something to the effect of “the sniffing of death”.) In the plaza, back in 1964, Che had the aura of a man of destiny, and it seemed entirely fit- ting that he should make a beautiful corpse. Except that they did cut off his hands, you know.

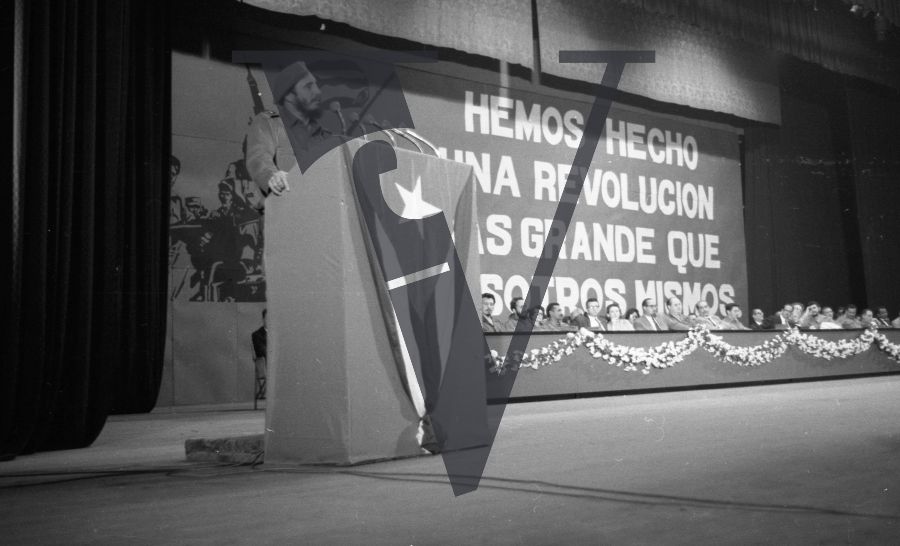

Fidel still unshaken, had been made even stronger by American hostility. The Congress of Intellectuals was a gathering of left-wing writers and academics, preponderantly Hispanic, but with an international cast as well. I remember overhearing a conversation between British playwright Arnold Wesker and poet Adrian Mitchell about the artistic value of the Beatles (Wesker against, Mitchell for). The very use of the word “intellectuals” seems pretentious in Anglo-Saxon society, but it comes naturally to Latins. I tend to side with the anti-intellectuals, always suspecting a “trahison des clercs” that can rationalize any evil—the support of the Iraq war by the current head of the Liberal Party springs to mind in Canada. The most uplifting moment for me was to hear a delightfully crochety C.L.R. James, the great Marxist writer from Trinidad, stand up in the assembly to denounce the luxurious treatment the delegates were receiving, in contrast to world poverty. He proposed that all intellectuals should be abolished as a force. His was a lone English-language complaint in a sea of Hispanic support.

Together with me were my frequent Swedish film partner, Staffan Lamm, and my wife Joy, who was recording sound. Very quickly we ran foul of the authorities. Being restricted about where we could film in the auditorium, my wife sat down with the equipment while I went to explore alternatives. This was interpreted as a sit- down strike. I was detained when filming in the port—this was forbidden. Money due from UPITN did not arrive—pulling out an old cablegram, it reads:

“UPITN. No money received. Situation critical. Cable $500 soonest….”

Deciding to move to a cheaper hotel, I found the Hotel Nacional where we were staying had charged us for meals we had not had, and my refusal to pay antagonized us further with the authorities. Defeated, we moved to a run-down hotel in old Havana while we tried to get a plane out. Finally, at the airport, going through customs before leaving, I had an altercation with a customs official who made fun of an item of feminine hygiene belonging to my wife, which antagonized the customs agent. The final straw was when they wanted us to leave without our film equipment. I balked at that, and the plane left without us.

We were driven by an armed soldier to a street in Old Havana, where we stopped outside a nondescript building. Inside stood an armed guard, beyond him a hip- high barrier, behind which stood a number of people, white and black, who looked at us curiously. We were taken into an adjoining room where an officer in dark glasses sat behind a desk. Our bags were dumped beside us, our passports placed on the desk of Dark Glasses, who looked at us for a moment, and then sank into deep contemplation. Very angry, I stared at Dark Glasses for some time. Eventually, he became aware of my gaze, for he seemed to take a decision, and beckoned me towards him. Standing at the desk, I gazed down into the glasses that reflected nothing. He began to speak, and the gist was that we were to stay there until they decided what would be done with us. It finally dawned on me that we were under arrest, and this was a prison.

“I want to call my Consulate.”

“I will tell you if you can call the Consulate.”

“It is my right to call the Consulate.”

A little wearily, as if I had been playing a tiresome game, Dark Glasses addressed the naughty child: “Now let us talk about the facts as they are. You have offended the Revolutionary Government, and have to stay here. If I decide to let you phone, I will tell you.” “Oh, I see. This is a punishment.” I was too angry at this added humiliation to be scared. After a while, one of the soldiers came over and told me it would be better if we went to the other side of the barrier. The room we entered was filled with men, and my wife was separated to a different room.

Thus began what was my most pro- found lesson in the nature of power. We had in effect been disappeared—no one had been informed. I would be jailed again in other countries for offending someone or something, but this first experience was the most frightening, for we did not know when or if we would get out. We were in the Calle Picotta Immigration Prison, effectively in limbo. Talking to the other prisoners offered no encouragement. Some of them had been there for years, each had a story to tell, all of which I had to take at face value.

There was an American, who claimed he had sailed his yacht into Cuban waters, and been detained. There was a young Swede, a Mexican, and a Greek. An elderly Dane, clearly mentally disoriented, said that he had been arrested while searching for gold on the Isle of Pines—a very strange tale. Another man, a mild-mannered Panamanian, had been a socialist professor teaching at Havana University. But the all-powerful authorities had not approved of the brand of socialism that he practised, and he had been evicted from his house, his passport seized, and sent here. He could not have been in Cuba without good connections in the Party. He told me he had written a letter to Fidel, which he had given to a guard. He later found it in a waste-paper basket, torn to shreds.

The group of eight Haitian fishermen had the most poignant story. Some years earlier they had been caught in a hurricane, and shipwrecked on Cuba. Since there were no diplomatic relations between Haiti and Cuba, the Cubans did not know what to do with them, and finally had set them to work cutting cane. The Haitians had found the conditions so abominable, that they had gone on strike. And this was where the Cubans had dumped them. Worst of all, among them was a woman, who had given birth in prison. My wife was put with her and the baby. There was a communal washroom, and every morning, without any prompting, one of the Haitians would stand guard over it while it was being used by the women, an infinitely delicate gesture.

The double bunks we used were filthy. We were given one sheet, and no blankets. The professor told me his sheet had not been changed in six weeks. On the walls were graffiti dating back to the old regime, the attacks on Batista’s repression now seemingly equally applicable to Castro. The second night I was there, I went to sleep listening to Fidel’s speech on the radio; when I woke up next morning, he was still talking.

That day, the second in jail, things began to change for us. A character who might have stepped straight out of Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana appeared at the door. A Jamaican in a panama hat and white suit, he worked for the British Embassy. It seems that the Embassy had learnt about our plight from a young Cuban woman who had gone with us to the air- port to say goodbye. Seeing that we did not board the plane, she had the acumen to alert the British Embassy. Across the barrier, the dapper Jamaican took our information, and left to report to the Embassy. The Cubans were in breach of an agreement with the United Kingdom about detention of nationals. That was the first sign of hope. The second came later that day in the form of Staffan’s father. Dr. Gustav Jonsson was Sweden’s most famous child psychiatrist, and a Communist sympathizer. He was currently a guest of the Congress of Intellectuals. Somehow, he had found out that his son had been jailed, and, translator in tow, he had tracked us down, to the clear humiliation of Dark Glasses. Seeing the baby there, Dr. Jonsson came back the next day with a bath and other things for the baby’s comfort, an added humiliation to our captors.

We were clearly on a fast track for release. I gathered letters from those prisoners who wanted me to send out appeals, from the Haitians, and from the Panamanian professor. We were taken to a plane the next day, and left. When the British Ambassador demanded an explanation for our detention—we had become a diplomatic incident —the Cubans charged us with “gross lack of respect”. Our equipment was shipped separately, via Poland, but we did get it back. When I arrived back in New York, where I was living at the time, I apologized to UPITN for coming back empty-handed, but they said they were happy with the story we had given them. Some days later, a neighbour told us the FBI had been around asking questions, and she had told them to speak to us directly. They never did.

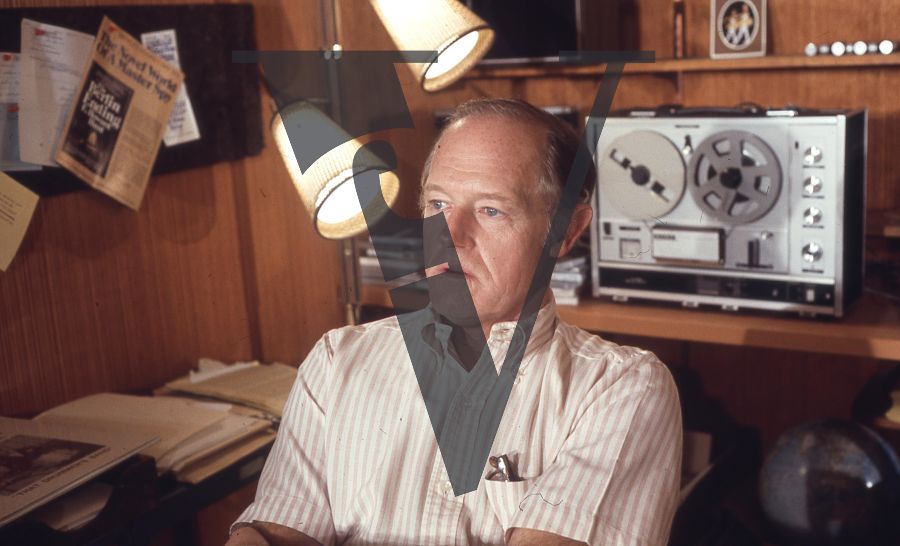

I wasn’t quite finished with Cuba. Some years later, Staffan and I did a biography of E. Howard Hunt, architect of the bungled Watergate break-in. Hunt had been a CIA operative (we called the documentary Paperback Vigilante, because while he was working for the CIA he nurtured a rich fantasy life writing thrillers about the Cold War). As an operative, Hunt had been involved in the overthrow of the left-wing government of Guatemala in 1954. He told us that Che, who had been captured there, only escaped execution through the intervention of another CIA operative. Hunt wanted to have Che terminated, and was regretful of this opportunity lost. Later, Hunt was involved in the Bay of Pigs invasion, designated to fly into Havana with a new American-backed junta when Castro was overthrown. He was unforgiving towards Kennedy, who he blamed for the invasion’s failure.

Paperback Vigilante took us to Miami, where Hunt lived, and we witnessed close up the malignancy of the Cuban expatriate community towards the Castro regime. This community had produced numerous terrorists who found safe haven and ready financing in the United States. Castro’s Cuba, almost from its inception, had been faced with terrorist attacks and a severe economic blockade; inside the country, the response had been vindictive, with the persecution and jailing of thousands of dissenters, including even Seventh Day Adventists. This would be defended by Castristas as their form of “homeland security”, the same rationale the Americans give for the abomination of their prison at Guantanamo Bay at the far end of the island. In the immigration prison of Castro’s Cuba, the prisoners were the victims of a callous indifference. Because the experience was brief, I do not regret it, but regard it as a salutary lesson, a glimpse into that dark side of nations, whatever the ideology, where all is permitted in the name of fending off a greater evil. Until it becomes hard to tell which is the greater evil.

….